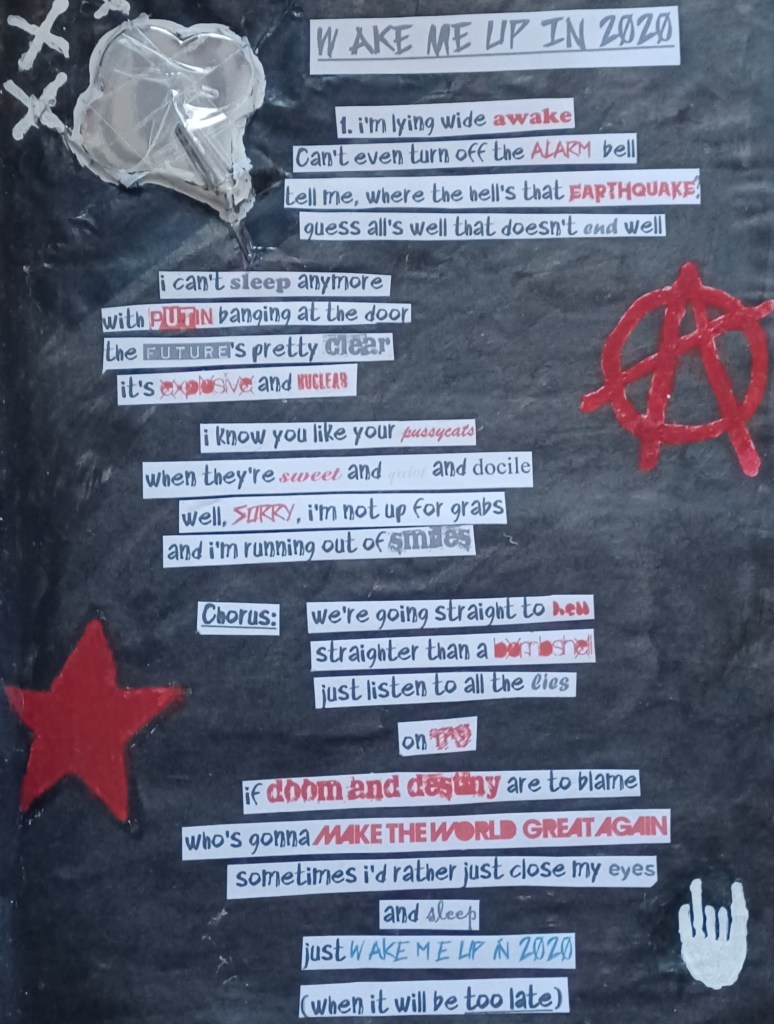

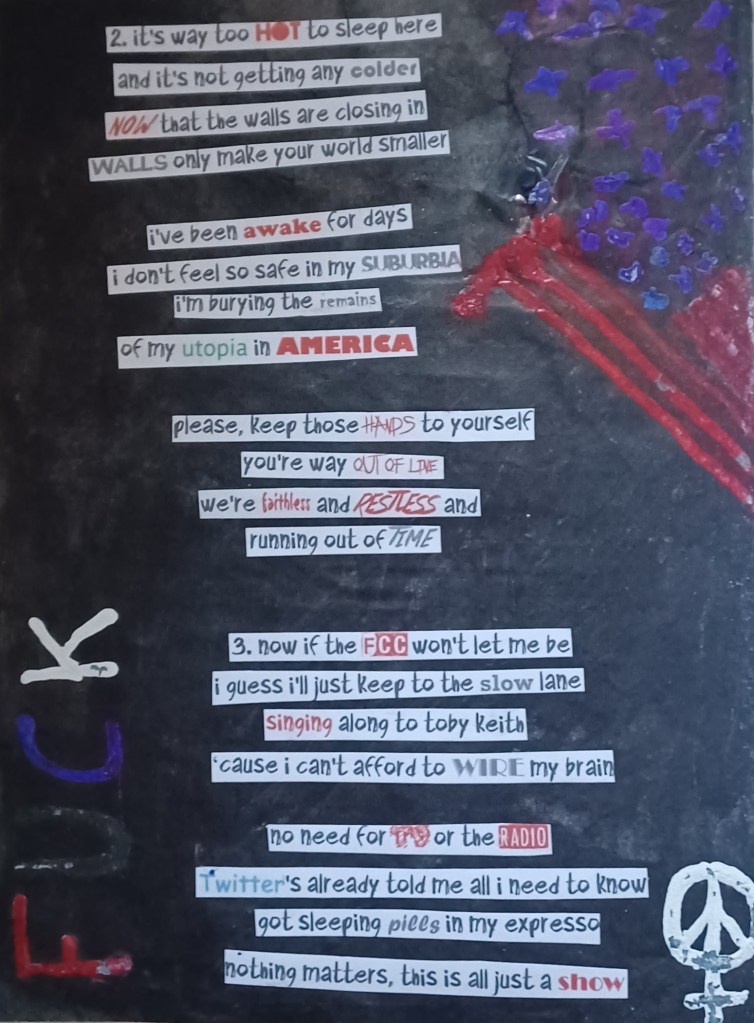

Pop-Punk Song For a World That Never Was

Written back in early 2018 (I think?), way before Covid obvs

Written back in early 2018 (I think?), way before Covid obvs

I’ll try to keep this one will be short(ish) but it will be full of interrogations, as I too am.

In the past few years, we’ve been talking a lot about cancel culture, especially with the emergence of social media – and what I really mean here is Twitter. Though the phenomenon draws from historical precedents, it can be safely said that the practice has really entered the mainstream from the moment Twitter became synonymous (no matter how erroneously) with “the people”.

Without making a habit of it, I’m going to look at a dictionary definition (Merriam-Webster’s) of this catch-all term: cancel culture is “the practice or tendency of engaging in mass canceling as a way of expressing disapproval and exerting social pressure” as well as “the people who engage in or support this practice”. Described this way, it’s hard to see the difference between this and censorship though there seems to be one key difference: it is supposed to come from the people and not the government.

The questions of who this “people” – or perhaps rather these people – may be is a whole other issue. Nowadays, the expression is found mostly in the declarations of conservative, right-wing supporters who use it to complain about the criticism and the attacks that they receive from (often younger) progressive left-wing supporters (also known as “woke”, as our dear Blanquer knows very well…). The idea is that these progressive people would track the words and actions of pretty much any one, ranging from anonymous citizens to famous figures, and even more so, it appears, those who have voiced progressive views in the past (J.K. Rowling, for example, used to be a fervent Trump and Brexit criticizer, until she revealed her transphobic views to the world). Then they would try and find those they could deem problematic (that is to say, racist, misogynistic, LGBTQ-phobic, etc) and then decide that these people become canceled: audiences must not engage with them, they should be banned from cultural acknowledgment, excluded from the public sphere, etc. Some of these social justice warriors, as detractors like to call them, even encourage bullying and real-life violence. Of course, most of you already know that.

Without going into details over a specific case, the practice has undoubtedly proven efficient in the past few years and it has led to significant improvements such as with Harvey Weinstein. However, and I am aware that I am stating the obvious here, it has many, many problematic aspects. To keep it short, in many ways, it is a 21st-century form of puritanism in which the notion of “innocent until proven guilty” is no more; there is no possibility for an individual to say things and then change their minds, or be uninformed at first, or learn new things, or improve, or be clumsy; each and every one of us must pick a side – “you’re either with us or against us” as they used to say around 2003; there is no notion of a nuanced opinion – and everything leads to Nazis and Hitlers, as Godwin predicted; opinions themselves have been conflated with people and their identity – you are what you say, whether you meant it as such or not; and, finally, many people do not seem to care about carrying a discussion anymore, or even convincing others with arguments so that they would change their minds rationally and not just to avoid people’s rage. Basically, cancel culture sucks, very much so. Wherever it’s coming from and towards whomever it is directed. But it’s easy to forget that sometimes, especially when you find yourself particularly detesting the views of certain people (looking at you JKR, your betrayal still cuts deeply) or even feeling threatened by them (talks of civil wars in numerous Western countries…)

That’s why, I always try to remind myself of the one case that hits very close to home

As you may know, the (then Dixie) Chicks faced an embryonic form of cancel culture after their singer Natalie Maines dared to face an anti-war opinion at a concert on foreign soil (London, the only part of her statement that the Guardian reported on at the time was “we’re ashamed the president of the United States is from Texas”, hardly a strong political statement…) I am not going to recap the whole thing and the trauma it left them in, their documentary Shut Up and Sing does that very well. But what we need to remember is that they were insulted on national television (“These are callow, foolish women who deserve to be slapped around”, “the dumbest, dumbest bimbos I have ever seen” “the Dixie Twitz” “Dixie Sluts”, etc cf their Entertainment Weekly cover), people organized online to stop radios from playing their music (an organization called the Free Republic) and to gather people to destroy their records publicly or to attend their concerts just to boo them, they received death threats and the Senate Commerce Committee even examined the whole situation. All of this culminated into one very real death threat that had the FBI investigating the attendees of a Dallas concert in 2003. To this day, almost twenty years later, most country platforms still pretend they don’t exist and many of their listeners see them as traitors, even though they were proven right in their rejection of the Iraq war. Of course, the “incident” – as they have come to refer to it – has also had a profitable effect on their career as it allowed them to embrace progressive views more freely and to establish themselves as defenders of free speech. Probably the main reason that their Taking the Long Way (my favorite album of theirs) won no less that five Grammy Awards in 2007.

The takeaway from all this for me, is how can I defend a system that almost destroyed my favorite band? Why is it that I can get behind cancel culture when it suits me but not when it doesn’t? Shouldn’t I treat my neighbor as I treat myself? Shouldn’t I treat those people who disagree completely with me just as well as those who don’t? How can I decide what is the moral code on which we should all agree? Is there even one? (There must be, I can’t get behind any form of discrimination or violence) Can’t we disagree without it being an aggression? So many questions, so few answers. Or simple ones, at least. I must admit that I don’t know.

The Chicks released a song alongside their documentary. It was recorded for Taking the Long Way but they kept it for the film in the end. It’s called “The Neighbor” and it says “Come out in your backyard Monday / Let’s meet on your front porch Friday”.

S’il y a bien une exception culturelle américaine – dans le sens où ce pan de la culture américaine n’aura jamais vraiment franchi l’Atlantique – c’est la musique country.

J’ai toujours trouvé hallucinant de voir à quel point des personnalités aussi importantes que Dolly Parton, Tim McGraw ou George Strait sont complètement inconnues en France (et m’étaient moi-même inconnues avant l’âge adulte). Ces derniers – à part Strait qui n’est plus de ce monde – pourraient se balader dans n’importe quelle rue parisienne sans attirer la moindre foule alors qu’ils remplissent des stades en Amérique du Nord. Quoique Dolly Parton aurait peut-être du mal à passer inaperçue si elle conservait son look de scène… Et que dire d’une immense star comme Carrie Underwood, par exemple ? Ce nom qui est pourtant celui de la gagnante d’American Idol ayant vendu le plus de disques, bien avant Kelly Clarkson (grande amatrice de country également, mais qui est connue en tant qu’interprète pop-rock en France) ne fera pas ciller grand monde par chez nous, ni le nom de sa chanson « Jesus, Take the Wheel » à laquelle j’ai pourtant vu une allusion dans la série Gossip Girl par exemple. Quant à Nashville, à la CMT et aux CMAs, n’en parlons même pas. Inconnus au bataillon hexagonal.

Parmi les figures faisant exception (tiens donc, ce mot encore), on peut penser à Miley Cyrus et Taylor Swift ainsi que Shania Twain. Néanmoins, les deux premières ont surtout pu passer la frontière culturelle grâce à la culture Disney Channel et l’appétence du grand public pour les détails de leur vie privée. De plus, et c’est aussi vrai pour Shania, leur musique a été « popisée » afin de plaire davantage aux oreilles européennes. Le cas de Taylor Swift – phénomène musical que nul ne peut méconnaître désormais – est d’autant plus particulier que son véritable succès en Europe (au-delà de quelques titres comme « Love Story » ou « You Belong With Me » qui sont arrivés en version pop-rock) s’est fait une fois que son virage vers la pop, puis plus tard la folk, s’était déjà suffisamment amorcé pour faire oublier « Picture to Burn » et « Tim McGraw ».

Il est paradoxal que cette musique ne soit pas plus connue quand on voit la passion du public français pour les westerns et les cowboys, par exemple, et pour tout ce qui a trait à l’Amérique (et non les Etats-Unis, il y a nuance !) en général.

Par-delà cette ignorance, il y a aussi les clichés qu’inspirent le nom même de la musique. A son entente, les gens pensent « Cotton Eyed Joe », saloon, line dance, chapeau et bottes de cowboys et banjo. Pourtant, ce dernier avait, encore récemment, été mis au ban de la musique de Nashville car considéré comme trop ringard. Par ailleurs, la line dance – bien que liée historiquement à la country – ne s’y limite pas et n’est pas dansée par une part si importante des fans de country. Ne parlons même pas du saloon et des vêtements de cowboys. Quant à la musique en elle-même, elle n’est bien évidemment pas restée coincée dans les années 50. Et pourtant, pour qu’un artiste country passe la frontière, il faut qu’il soit réétiqueté « folk », « rock », « blues » ou à peu près n’importe quoi d’autre. Ainsi, tout le monde ne penserait pas forcément à y lier Johnny Cash, the Eagles ou Neil Young en France.

Evidemment, il y a aussi le fait que la culture country est particulièrement conservatrice et ségréguée, ou bien tout du moins qu’elle l’a été ces dernières décennies. Ségréguée, pour ne pas dire franchement raciste (pensez Beyoncé aux CMA 2016), misogyne (pensez traitement des Dixie Chicks en 2003) et homophobe (pensez Lil Nas X). Non pas que cela soit représentatif de tous, ni que ce soit une fatalité, bien évidemment, mais il est certain que le monde de Nashville s’est replié sur lui-même ces 25 dernières années. L’auditeur moyen – du moins selon les radios country, et donc l’auditeur pour qui elles conçoivent leur programme – est un homme hétérosexuel blanc qui vit au Sud et vote Républicains entre deux weekends de chasse et de fête à l’arrière de son pick-up.

Mais le succès incroyable d’« Old Town Road » ces dernières années ainsi que celui de Mickey Guyton et sa chanson « Black Like Me » sauront peut-être permettre la rédemption de la country et son rayonnement au-delà des frontières américaines…

No more chess, no more queen’s gambit, thank you

Now’s the time for sudocoups

Fuck fake news and fuck you too

Open your eyes and join the queue

*

It’s time to crash this party

Pick a side or a bone

It’s time to pour the tea

Take a red pill or a pillow

*

The message’s pretty clear

It’s written in capitol letters

The future, the end is near

It can only get bitter

*

All things seem confirmation

Bros and urobros

All of us high on information

Stuffed sick with sloppy joes

*

I wonder who started that caravan

That small town serenade

That storms and drops

Into darker days

I’m completely blown away by what we are seeing in the US right now – and really all over the world, including in France – so many people coming together to protest against racism and police violence. It’s incredible to watch history in the making and it fills me with so much hope for the future.

Which reminded me of this text I wrote about three years ago, after seeing a sticker on somebody’s bag at my uni’s library:

Goodnight

Say goodnight

White pride

We’ll be alright

In the tide

*

What’re you so afraid of?

People coming together?

Or is it friendship and love?

That whole world outside your little self

Don’t you know?

This world’s only ever been grey

And you only grow

If you live for today

If you open your hand

*

We will be one

No matter what you say

We’ll fight everyday

With stories and songs

Hate’s not meant to last

You’re living in the past

Say goodnight

Because you know

Say goodnight

That tomorrow

Will be ours

I did not leave the US because I was afraid of catching it. I did not leave the US to go back to my friends and family. I did not leave the US because I suspected places might remain closed until the end of my visa. I did think all these things. But they are not the true reason for which I left the US. I left because I knew there would be a disaster in this country.

We knew from mid-to-late February that the virus was definitely coming, and we were preparing ourselves for the possibility of schools closing and the need to start working from home. When I became sick with an infection in late February, I was able to witness first-hand how the health services were preparing for a wave of sick people, just as I could see on social media how France was telling its population to self-isolate if they were experiencing symptoms or knew somebody who was, and to call their doctors instead of going to the ER and risking mass contamination. Still, at that point the virus still seemed like a disturbance rather than the source of a worldwide crisis, and I remained excited for the months I still had to spend in the US, enthusiastically planning new trips and visits.

I started suspecting that things were going to get bad a little before mid-March. By then, my social media newsfeeds has begun to be flooded with information and videos from Italy, a lot of them consisting in warnings for other countries. They were telling us how they were painfully learning that the virus was much more dangerous than we initially thought, back when it only affected Asian countries and rare tourists; that it was much worse than the flu and that it wasn’t only the elderly who was dying, though they did constitute the majority of the victims. At this point, the situation in France was slowly escalating into a national crisis as more and more people were getting sick (with not too many dying yet, still) and the government started changing their discourse. Day after day, they started introducing new restrictions, banning large gatherings, cancelling cultural events and asking people to limit their travels. All the while reassuring us that we did not need masks (of course, the truth was that we didn’t have any) and that there was no need for schools or places like Disneyland Paris to close.

I think that, paradoxically, it was the US ban on European travelers that gave me a first signal that something huge and unprecedented was brewing. When my father had first mentioned it, about a month earlier, I was utterly convinced that it was impossible, that the US would never do such a thing, that globalization was too big to be stopped. It would not take long for me to understand how mistaken I had been. Two days later, OUSD was finally closing all of their schools (at first only for a few weeks), days after San Francisco and Berkeley had made the same decision.

Then, as I watched the wave wash over Europe, and European leaders taking unprecedented measures, I started realizing just how bad it would be. From then on, lockdown made total sense to me and I resolved to comply with all these necessary restrictions. When Macron gave his “we are at war” speech, I knew that his tone was appropriate. I had finally stopped underestimating Covid-19. But, unfortunately, the same could not have been said for many Californians and Americans around me. They didn’t know their country would be hit harder than it had ever been since 1929, or maybe ever. They did not know that it was already too late to avoid a tragedy.

There were several factors that made me realize a little earlier than others (but probably way later than experts) that the US would be hit differently than other Western countries. Some of them have to do with current politics, of course, but some are also deeply engrained in the American culture and its policies (or lack thereof), for which we could not really blame the current administration.

First, as I mentioned it previously, I had one advantage over most Americans, and it resided in the fact that I was not American. This fact, which would not have mattered all that much in other circumstances, meant that I had a vantage point. One that had to do with social media and the way they work. Because my social media accounts are considered “French” – based in France, where I usually live – because I follow a lot of French or European media and people, because most of my online friends are French or European, most of what I saw on my social media newsfeeds could not have been seen by Americans. Instead of watching mostly CNN or Fox News reports – which had a lot to do with the primaries at that point – or reading from my relatives in such or such American state, most of what I was seeing related to the epidemic and its devastating effects on Europe. I was seeing warnings from this friend met in Oxford who now lived in Italy, I was seeing French celebrities and officials get sick one by one, I was seeing dozens of videos of health workers begging people to stay at home in order to save lives. I had a pretty accurate picture of what was going on in Europe and of the virus itself. And there was no reason why the US would not suffer the same fate, in fact it was already on the way. I was witnessing the future of the United States, and I was one of the rare people to do so at the time. Apart from a certain degree of denial, the American public remained largely unaware of the European situation.

This is not the only reason why many Americans did not see it coming. As of early 2020, the United States was, as many other Western democracies, in a state of extreme political polarization. Before Donald Trump’s 2016 election, but even more so after, bipartisanship and cross-parties cooperation had given way to a culture of staunch partisanship. I strongly believe that social media and their mechanisms that exacerbate both political opinions and division between opposing camps are to blame here. People used to believe we could build bridges, and now they want to build walls. They used to think democracy meant that a plurality of opinions was enriching, and now people are being “canceled”. There were consensuses, now there are facts and alternative facts. Everybody, and I the first, is willing to bend facts to their opinions and beliefs, instead of doing the opposite. In many situations, while we used to adhere to political parties and politicians according to the policies they advocated, it is now our adherence to a party, or at least our rejection of a party, which shapes and indicates how we feel about the world. This is not helping.

Because allegiance and personal feelings have started to matter more than consensual truths and expertise, because experts have now become, maybe sometimes rightfully so, the embodiment of a self-serving elite who cannot relate to the daily concerns of the common people, distrust and defiance against the media and scientists is greater than ever. They’re not the repository of knowledge and method that they used to be. They have become fallible oligarchs hiding their incompetence behind their degrees; at worst, collaborators, and at best, sellouts. Trump said that experts were “terrible”. But who should you turn to then? Self-declared, unproven experts, like him? Your gut-feeling? God? Twitter?

Of course, there is one critical factor I haven’t mentioned yet. Had this crisis taken place pretty much any other year, things would not have gotten that bad. But 2020 is a special year for Trump. It is the year of his only possible reelection – as of the current Constitution at least, you never know what can happen with this guy.

With his reelection on the line, both Trump – and Republicans – and Democrats are de facto acting and communicating strategically, with the goal of winning the majority of votes in November. Some may find this cynical, but it is how politics work, and it is the smart thing to do. Trump’s reelection campaign strategy revolved around the good economic health of the country and its historically low unemployment rate (basically the idea that he would have indeed made America “great again”, though how critical his policies were to this result remains arguable). However, all of this has been swept away by the Coronavirus. Instead, Trump finds himself with a historically high unemployment rate of over 20%, an issue which has forced him to resort to radical measures: stimulus checks. He thus loses one point of criticism over Democrats (notably Biden and Sanders): who’s the socialist now?

What this means is that it is in Trump’s interests to diminish the gravity of the crisis, to pretend that everything is fine and that he’s doing a great job (that also has to do with his egomania), and to reopen the country as quickly as possible in order to try and cut his losses. Hence the delusional Easter reopening. On the other hand, it is in the Democrats’ interests to exaggerate the reality of the crisis, and even to take advantage of the chaotic economic situation in order to show the necessity of “safety net” policies for which they have been advocating for years. The virus, and any analysis of Trump’s handling (or mishandling) of the crisis has therefore become a political argument. In such a context, is anybody even approaching some kind of objective speech?

Some people have called the Coronavirus crisis the new divide of American politics, to be loosely modelled on the preexisting divides between pro-Trumpers and anti-Trumpers, and Republicans and Democrats. The difference is that this last group may be more united than ever in this crisis, while the Trump camp may face defections.

It is mostly for this reason that Trump initially dismissed reports on the upcoming crisis and tried to shift the blame on others (among which China, Europe, the World Health Organization, the states and the Obama administration); only to change his tune when even he, the Denier-of-Proven-Facts-in-Chief, could not deny the reality of the crisis any longer. Of course, this comes as highly unsurprising, since, as CNN’s Chris Cillizza puts it, “What Trump is doing now is what he always does about everything: Attempting to rewrite history so that it looks like he was always the smartest guy in the room, the one person who saw this all coming from a mile away.” This translates into increasingly ridiculous White House briefings that showcase his mythomania more than ever and find him bragging about his disastrous response to the crisis and his unprecedented ratings. He has even adopted Emmanuel Macron’s military lexical field. Anything goes when it comes to avoiding losing face: unsubstantiated accusations, false reassurances, miraculous cures such as a more clement weather or chloroquine… All Trump is really sending is wrong signals.

Unsurprisingly, Faux Fox News has, once more, sided with Trump. Like him, they started by calling the pandemic a “Democratic hoax”, pointing the finger at China and Europe, and turning to the now usual claim that “the flu kills more people every year”. Now that the situation has become impossible to ignore, they’ve started inviting celebrity “doctors” like Dr. Phil or Dr. Oz to say crazy things live, such as comparing the virus to AIDS (that you can only get from someone’s blood) or car crashes and drownings (it’s true that these are highly contagious…). Of course, if that is what you call experts, it makes sense to question their competence. Such fallacious comparisons are served with the usual grossly exaggerated or undermined facts, a good chunk of various conspiracy theories, and outright imaginary figures. It’ll remain broke ‘cause they ain’t gonna fix it.

You put all these things together and what do you get?

A population more confused and divided than ever, who have no idea who and what to believe and what will really happen to them. Some people are in outright denial, some are panicking, some are deluding themselves in thinking that things are going to be okay, some are doing business as usual because they don’t have a choice… Apart from conspiracy theories (one of my friends thought it was simply deaths from the flu and that people were overreacting) some people are even actively counteracting measures and not taking social distancing seriously, which will only delay the end of the crisis and its impact.

If you add this state of extreme political polarization and misinformation to the complexity of levels of government in the United States, you end up with a patchwork of local responses to the crisis, which in the end prevents a coherent national strategy. Cities, counties and states are each coming up with their own measures, trying to balance the factors of health recommendations, economic needs and public approval, all the while adapting to their own local specificities.

It is too easy to put the blame of governors though. It was the federal government’s job to design this strategy and it is only Trump’s unwillingness to take responsibility that has led to local governments filling the void with what they thought would be better (for some) or blind loyalty to Trump and faith in market and religion (for others). Under the guise of supporting state rights, Trump is, as usual, shifting the blame in case of bad news. To summarize: if things get better, it will be thanks to his administration; if things get worse, state governments will be to blame. Overweight-and-totally-not-obese Trump doesn’t care about the real world, he’ll have his cake and eat it too. Apart from Trump’s egomania (what else is new?), the resulting patchwork of responses means that the crisis will be drawn out, probably even more than it would already have been in this continent-sized country. What we are seeing is only the beginning.

I remain unconvinced, however, that things would have been drastically better under the precedent administration. Sure, President Obama would have taken things more seriously and shown the responsibility of the highly competent leader that he is. But this level of partisanship is not completely new to the Trump era, at least on the side of the Republicans. Considering that President Obama faced an unprecedented amount of hate and dubiously justified criticism from them, it is easy to imagine that a measure such as a federal stay-at-home order would have been met with much hostility and defiance. People would have accused him of acting like a dictator and suspicions of a conspiracy (the famous “Democratic hoax”) would have been rampant. Then, how would the Obama administration have faced calls to reopen the country?

Nonetheless, President Obama would have acted with dignity and dutifulness, two qualities foreign to Trump. There would not have been any outright lies or coddling, no self-congratulatory statements, but plainly stated facts and hard, sobering truth. Unlike Trump, Obama would have cared more about the well-being of American people than about his popularity or his reelection.

But most of all, the problem resides with the American society itself. You cannot change a whole country in a matter of weeks, and the best measures would only amount to a patch on a long-running blowout. This doesn’t have much to do with Obama or Trump. The truth is that the American way is failing and needs to be thoroughly remodeled, without which it will meet its end. It’s time to put a little equality in all that freedom.

In many ways, the richest country in the world looks like a third-world country. The lack of safety net has kept a huge part of the population in poverty, or on the verge of poverty, for decades. No other developed country has so many retired people forced keep working in order to eat or so many illegals occupying key jobs in industries (especially the food industry) while retaining a precarious status. An unofficial socio-economic segregation has kept African-Americans in dire situations, with little prospect of improvement. And it’s not getting any better, with or without the virus. Inequalities are rising and the wealth gap has never been so big, never has there been such a big homeless population in places like San Francisco or Los Angeles. And now, with the unemployment rate skyrocketing, more and more people will find themselves dependent on food banks, or losing their home, or unable to borrow money and to get healthcare.

Healthcare access has historically been a problem, and it will only get worse as people lose their insurances along with their jobs. And even those who do have an insurance are in no way guaranteed a cheap – let alone free – care. The system is well-established, and everything has been designed to make the patient pay as much as possible and make the insurance and the hospital as rich as possible. These people with little to no coverage have been discouraged from taking care of their health for years. This has made them chronically fragile and they will be the first ones to die. Not to mention the rates of obesity and diabetes (among which, probably, Trump himself). Everywhere I look, all I can see is a health disaster. And it’s even risible when one looks at the amount of money being injected in the health industry every year. I don’t know where it goes, but I know that nurses in New York had to wear trash bags to work and that nobody seems to have enough tests.

And then, I remember that, in this country, people are allowed to carry rifles as a constitutional right. And that the notion of a popular upheaval against an autocratic power that does not defend the interests of the people is culturally valued. And that a lot of people are bound to get angry in the next few months, for a lot of reasons…

This is why I left.

The Coronavirus did not wreck America. America wrecked itself. The crisis only precipitated a tragedy that was coming anyway. It did not so much worsen the wealth gap in the country as it revealed it, in all its ugliness. What will happen to these people, those who will survive only to find themselves bankrupts? And what will become of this country, once so glorious and powerful? I cannot help but think of Renaud’s line: « Ce pays que j’aimais tellement, serait-il/finalement colosse aux pieds d’argile ? »

This leaves me with a lot of interrogations: What is freedom? What are its costs? What is democracy worth when confusion, misinformation and lack of education seem to pervert its principles?

But, most of all, these observations leave me with a bitter taste, one that truly makes me sick. So many deaths that could have been avoided, so many more to come…

To be continued…

Alors que je marchais autour du lac Merritt, une phrase entendue au hasard m’a inspirée, et puis je me suis imaginée en quarantaine pour le coronavirus, comme cela risque d’arriver bientôt.

Je n’ai réussi à écrire que des fragments :

Ne voir du monde que son reflet

A la surface d’une flaque d’eau

Se pencher à la fenêtre

Pour n’en percevoir que les échos

*

“Whatever. I’m trying not to obsess about it.

And failing, obviously.”

When the world ends, at least

I will have had my words

*

In questi tempi di fame

Per qualcosa più grande

Per una forma di fede

L’unica cosa che c’è

È il cielo sopra di noi

Il cielo sopra di noi

Il cielo sopra di noi

Il cielo sopra di noi

Il cielo sopra di noi

*

Trying to hold onto me

I can’t hold onto me

Attention, je parle ici bien de culture consumériste. Dans le sens « société de consommation » et non “consumer society”. On voudrait nous faire croire que cette société nous appartient, qu’elle est synonyme de notre liberté, sans doute même partie intégrante. Comme si cette société n’était là que pour servir le consommateur. Certes, elle tourne bien autour de lui. Mais il est plus souvent le dindon de la farce.

J’ai tout de même le sentiment qu’on est bien mieux lotis en Europe qu’aux Etats-Unis. Déjà, je trouve que le consumérisme est bien moins omniprésent. Je pense aussi que le consommateur européen est mieux informé et protégé que le consommateur américain. Parmi les obligations légales qui nous facilitent la vie et qui me manquent tant aux Etats-Unis :

– l’affichage des prix au kilo dans les magasins : il est tellement plus facile de comparer le prix de deux produits lorsque cette information est indiquée et qu’on n’a pas à la calculer soi-même, surtout quand le packaging mentionne aussi une quantité gratuite pour bien nous embrouiller encore plus

– la composition des produits indiquée en pourcentage : bien sûr, en France aussi ils aiment nous indiquer leur composition « par portion », portion qui est totalement aléatoire et arbitraire, et à laquelle on aime souvent rajouter – notamment sur les paquets de céréales – une quantité tout aussi arbitraire de lait, histoire de bien rendre les chiffres incompréhensibles. Heureusement, il y a toujours cette colonne « pour 100 grammes » qui permet d’y voir un peu plus clair

Deux autres exemples aussi insupportables pour une européenne, mais bien plus justifiés : les pourboires (liés à l’absence de revenu minimum digne de ce nom dans la restauration ainsi qu’à une habitude culturelle profondément ancrée) et le fait que les taxes ne soient jamais incluses dans les prix, sauf pour l’alcool (elles sont trop fluctuantes, et encore une fois cette habitude est bien ancrée pour les américains). Je déteste cette impression constante de me faire avoir car je dois toujours payer plus que ce dont j’avais eu l’impression au début.

Exactement trois mois que je suis aux Etats-Unis. Je le soupçonnais par le passé, mais je le sais désormais : ce pays n’est pas pour moi. Je l’aime pour son exotisme, pour ses excès, pour la fascination qu’il exerce sur moi. Mais ce ne sera jamais mon chez moi.

J’ai remarqué plusieurs grandes tendances qui font partie de ce que certains appelleraient la « mentalité » américaine. Je les connaissais déjà toutes plus ou moins, notamment à travers mes cours de civilisation américaine, mais désormais elles se vérifient.

L’une d’entre elles c’est la notion de danger comme quelque chose de familier, voire même de normal. Dans ce pays, le danger, sous toutes ses formes, est omniprésent. On est en danger à cause du port d’armes. On est en danger à cause de toutes ces substances chimiques utilisées dans l’alimentation ou d’autres produits de consommation. On est en danger à cause de la criminalité qui est relativement banale (en particulier à Oakland). On est en danger si on se promène seul le soir dans la rue. On est en danger car des animaux sauvages vivent à deux pas. On est en danger car les accidents de la route sont bien plus courants. On est en danger car sur la route il n’y a pas toujours de trottoir pour circuler en toute sécurité. Et ça fait partie de la vie, c’est simplement une réalité à accepter.

Une autre notion omniprésente et qui m’est difficilement supportable : la société de consommation. Les Etats-Unis sont un pays capitaliste, et gare à qui tenterait de l’oublier. Les injonctions à consommer sont partout dans la rue. C’est ça le rêve américain : la liberté de consommer. Tout n’est que magasin ou restaurant. Tout n’est que marque ou chaîne, standardisé au possible. Et si la marque est trop chère, ce n’est pas grave, il y a une solution pour ça : les magasins au rabais. On y achète aussi des marques mais moins chères. Comme pour dire aux plus pauvres « ça ne fait rien, vous aussi vous pouvez faire partie de la fête de la conformité. Et plus tard, quand vous aurez plus d’argent, vous pourrez vous payer la vraie marque directement. » “The real thing” Comme s’ils s’élevaient socialement et économiquement à travers leur consommation de marque. Comme si c’était la chose à laquelle on devait tous aspirer : posséder un t-shirt blanc uni uniquement orné du symbole tribande. Ça vend du rêve ! Tout est fait pour vendre et tout est bon pour vendre. Ad nauseam.

Un autre problème que j’ai avec le capitalisme c’est que tout est ramené à son prix, à ce qu’il peut rapporter. Ce système universitaire et ce système de santé – bien plus étroitement liés qu’on ne le pense de prime abord – qui essaient de faire un maximum de profit, excluant au passage les plus défavorisés. Quelle plus-value va-t-on pouvoir faire sur chaque compresse utilisée pendant l’opération qui sauvera une vie. Quel examen vaguement utile on va pouvoir prescrire au patient inquiet. Et comment on justifie les coûts exorbitants en évoquant la qualité du soin ou de l’enseignement dispensé. Comme si l’excellence devait se facturer.

Directement issu de ce capitalisme, l’esprit de compétition qui aggrave encore les inégalités. On note tout, y compris les écoles, et on inscrit son enfant dans la mieux notée, quand on a les moyens de se la permettre. Et puis du coup on demande à ce qu’elle soit financée, au détriment de l’école publique défaillante dont le niveau ne cesse de chuter puisqu’il n’y a aucune diversité socio-économique (ou raciale, puisque dans ce pays ce n’est pas un gros mot). La ségrégation a beau être interdite, il vaut quand même mieux que tout le monde reste bien à sa place.

Cet esprit de compétition qui s’infiltre dans de nombreuses autres situations. Les collègues qui se tirent dans les pattes au lieu de se soutenir, les gens qui dénoncent les autre pour des broutilles, et ce sourire toujours aux lèvres. Ce que bon nombre de français appelleraient de l’hypocrisie. Ce que bon nombre d’américains considèrent comme de la politesse.

Bien sûr il y a des choses que j’apprécie énormément dans ce pays, comme la variété de cultures, le côté avenant des gens, cette merveilleuse habitude d’organiser des événements collectifs, cette positivité dans l’éducation des enfants. Mais ça ne suffit pas à calmer ma nausée, celle qui me prend quand je vois tout cet individualisme et ce consumérisme.

Plus que jamais : je suis française et européenne, et fière de l’être. Ma place est en France, dans mon pays. Pas seulement mon pays de naissance, mais aussi le pays que désormais je choisis, parmi toutes ces autres possibilités. Celui dans lequel je reconnais mes valeurs.

C’est sûrement aussi pour ça que je suis si fascinée par les Etats-Unis. Pour leur différence qui m’interpelle, m’amène à questionner mes valeurs et mon modèle, et me pousse dans mes retranchements.